Juvenile Gannet Research

Juvenile Gannet Research by Jude Lane

Researchers from the University of Leeds have been studying the behaviour of northern gannets on Bass Rock for over two decades. It’s a really exciting time to be involved in seabird research as technology is constantly developing allowing us to learn about the behaviour of birds at sea in ever increasing detail.

Initially the research on the Bass Rock gannets involved making observations at the colony such as monitoring what time birds left and returned from foraging trips. Satellite tracking devices then became available allowing birds to be tracked whilst they made foraging trips, a great scientific advancement allowing us to see where they were going to find food. We now have many types of devices, often known as biologgers that can contain multiple sensors able to collect data on, for example, location, air pressure, whether the device is wet or dry and body angle. These biologgers are allowing us to study the behaviour of birds at sea like never before, gaining valuable insights into where they go and what they do.

Until recently the deployment of these devices has been restricted to adult birds rearing chicks; breeding adults are easy to catch and all but guaranteed to return to the nest enabling the logger to be retrieved and data collected. Birds that don’t return to the colony for several years, such as juveniles, are much harder to study and require the use of devices that transmit data via satellites. It’s also quite a gamble to deploy an expensive device on a young bird which might not survive. However, understanding the dispersal of juvenile seabirds and where they travel at sea is crucial to understanding how these young birds use the marine environment and how they might overlap with potential threats such as fisheries and renewable energy developments.

A pair of adult gannets will spend about 4.5 months each summer raising a single chick. From the end of August, the distinctive dark juvenile gannets can be seen standing with their parents around the colony. By about 13 weeks, they will be heavier than their parents and have reached the age where their parents will leave them to fend for themselves. This means the juveniles won’t get another meal until they head out to sea and catch it for themselves meaning a steep learning curve is required if they are going to reach adulthood.

_Maggie_Sheddan.jpg)

Mortality in juvenile gannets is high, however metal rings with unique identification codes fitted to the legs of juveniles have shown that they can migrate as far as West Africa in their first few weeks at sea. However, what these rings aren’t able to tell us is how they make this journey, how long they spend around the colony before they leave and how long the journey takes? Or, which routes they use?

So these were the questions we set out to answer when we attached solar powered devices which provide both GPS (accurate to 10’s metres) and satellite (accurate to within 1600m) locations, to 42 juvenile gannets in October 2018 and September 2019. In the same years we also attached geolocators to breeding adults so we could compare juvenile and adult migrations.

What did we find out?

After the juveniles fledged from the colony, they spent between 2 and 9 days floating on the water, too heavy and not strong enough to take off again. On the water they are unable to catch food, to do this they need to plunge dive so they need to lose weight and strengthen their flight muscles quickly so they can get airborne and increase their chances of survival. Once the juveniles started flying they spent between 2 and 4 days flying short distances in between resting on the water before starting to fly further away from the colony.

Migration

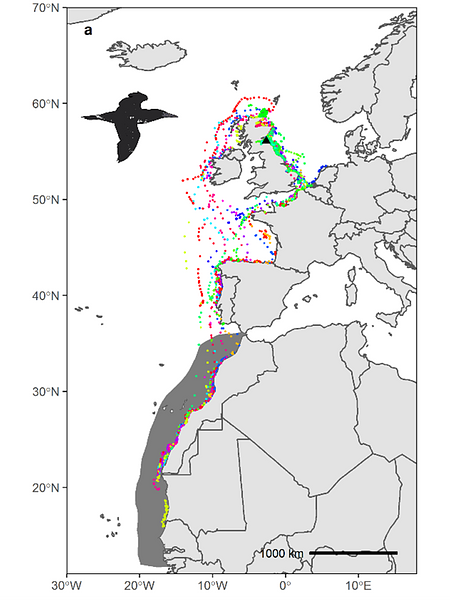

Both juvenile and adult gannets migrated as far as West Africa, travelling both clockwise and anti-clockwise around the UK. All the juvenile birds stuck very close to the coastlines where possible, remaining within approximately 15km of the shore unlike the adults that travelled further offshore. Here you can can see the tracks of the juvenile gannets, each bird is shown in a unique colour.

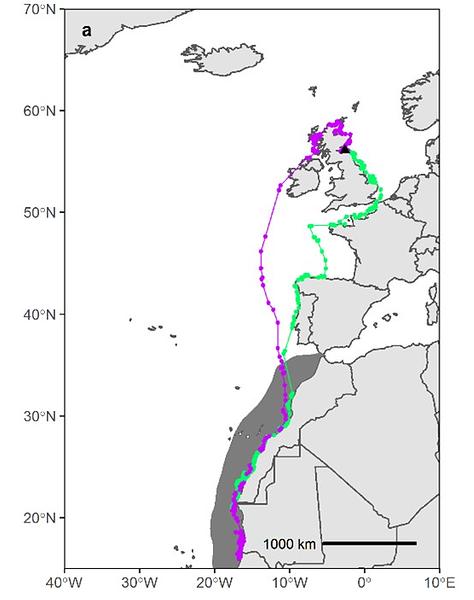

The juvenile gannets took, on average, 14 days to reach West Africa which was much faster than adults that took, on average, 58 days. The faster journey times of juveniles was primarily due to the younger birds sticking to the coastlines and therefore travelling shorter distances. Here you can see the comparison between 2 juveniles (top) and 2 adults (bottom), each bird is a different colour.

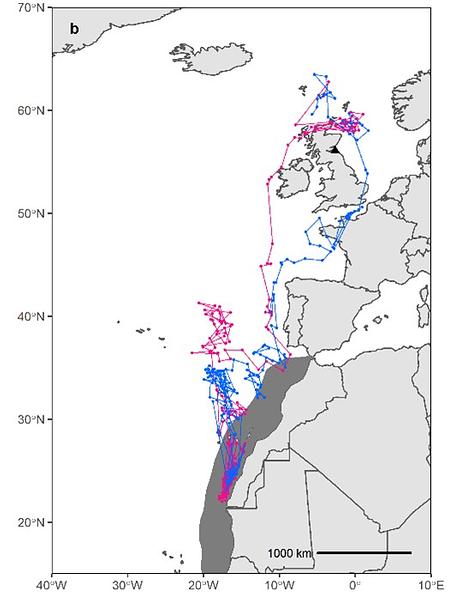

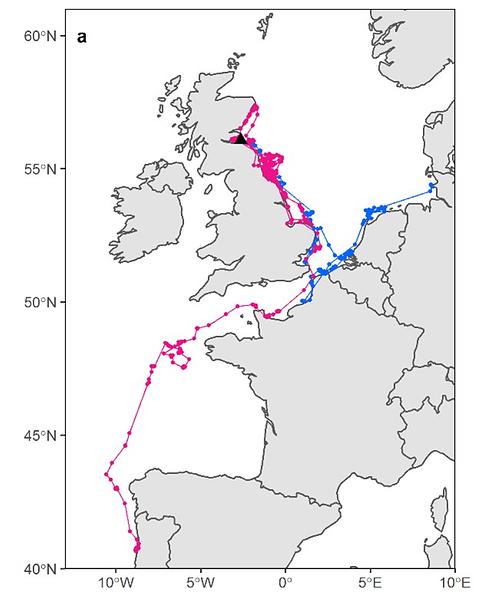

As expected the mortality in juvenile gannets was high, about 30% died within the time we were able to track them for. Interestingly we found that mortality was higher in birds that made multiple changes in direction such as the two birds (pink and blue) in the map below.

The waters off the coast of West Africa are known as the Canary Current Large Marine Ecosystem (CCLME; shaded grey in the maps above). The Canary Current LME is a very productive area of ocean important for many species of seabird but it is also a hotspot of illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing, posing the dual threats to seabirds of reducing available prey and by-catch, where birds get caught in fishing gear. Our work highlights the importance of the Canary Current LME for difference age-classes of seabirds and echoes previous calls to strengthen marine conservation efforts in this region.

This research has been published in the journal Marine Ecology Progress Series. If you’d like to read it and find out more, you can download the paper for free here.