_Eleri_Williams_(7).JPEG)

Mapping our local seagrass meadow

Read a summary of results from seagrass mapping work undertaken by Restoration Forth volunteers at Tyninghame.

By Eleri Williams, Restoration Officer

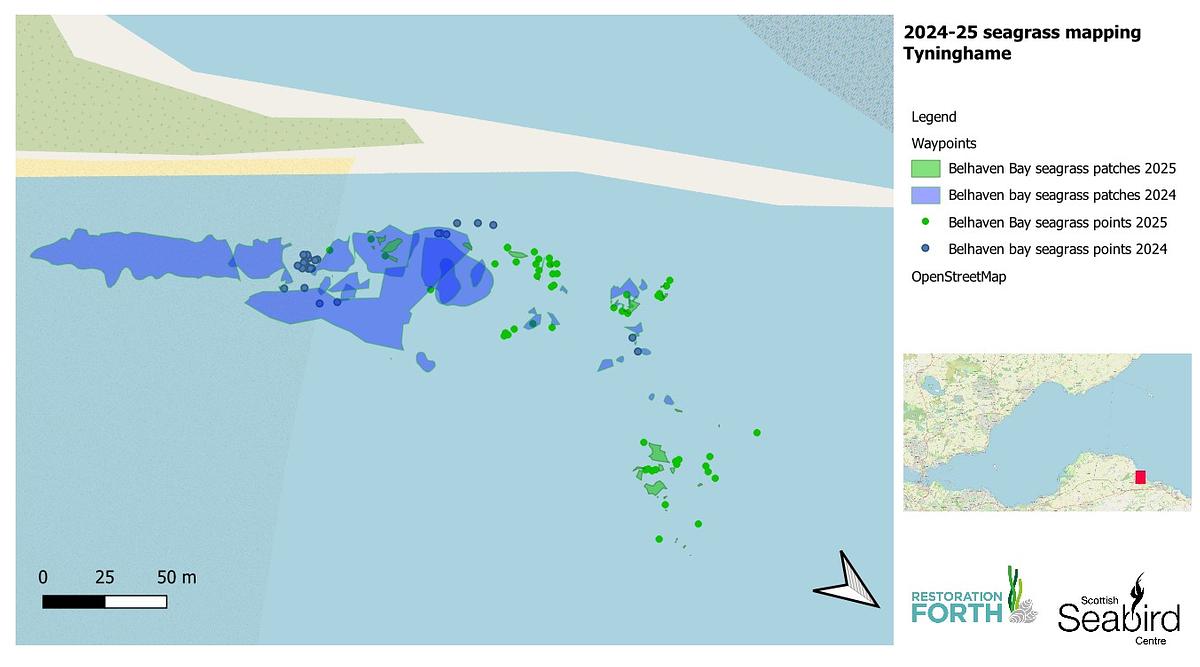

Across 2024 and 2025, the seagrass at Sandy Hirst, Tyninghame, was mapped with the help of 61 volunteers. The map above displays the spatial extent of both common eelgrass (Zostera marina) and dwarf eelgrass (Zostera noltii) in 2024 (blue) and 2025 (green). This map also represents a huge amount of work by our Restoration Forth volunteers over some beautifully sunny days in the past 2 years.

This data was collected on foot, by tracing the edges of seagrass patches with a handheld GPS unit. The generated GPS points form an outline of the seagrass patches, which can be used to form shapes when uploaded to a digital mapping software, such as QGIS. The seagrass ‘points’ on this map represent smaller patches of seagrass which are smaller than 30cm2. The patches which are bigger than 30cm2, are traced with GPS unit as well as measurements of length and width to get a rough idea of the patch size.

This map suggests that the seagrass extent at Tyninghame has significantly declined since 2024. Most of the large patches mapped in 2024 consisted of some patchy common eelgrass and some larger, denser dwarf eelgrass patches, particularly on the left of this map. However, a considerable proportion of dwarf eelgrass disappeared in 2025, which may have been caused by the overgrowth of gut weed (Ulva intestinalis) in summer 2024. Gut weed grows on top of the seagrass, blocking light from reaching the leaves and preventing photosynthesis, which causes the seagrass to die back.

It is important to note that long-term changes in seagrass distribution will occur over multi-year timescales. Although the data suggests there has been a significant reduction of dwarf eelgrass this year, it remain unclear whether the seagrass is annual or perennial, meaning that the seagrass may return next year.

On a more positive note, there was a good proportion of common eelgrass found well into the boulder field at Tyninghame this year. Although seagrass often prefers sandy, shelly areas, this seagrass showed some of the highest densities across the site, suggesting that the boulders provide shelter and stability for the seagrass.

.JPEG)

Seagrass mapping is a useful tool to observe changes in seagrass distribution over long-term timescales. Habitat distribution can change significantly from year to year depending on factors such as weather events and human disturbance. This is why habitat mapping is often conducted on longer timescales (e.g. every 10 years) to remove some of the annual variability. Although this map is just a small snapshot in time, it still forms an important part of longer-term habitat mapping at Tyninghame.

Who we are

The Scottish Seabird Centre is a proud partner of this WWF-UK led project that brings together expertise from a range of partner organisations including Project Seagrass, the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh, Heriot-Watt University, the Marine Conservation Society, the Ecology Centre, Fife Coast and Countryside Trust, Edinburgh Shoreline and Heart of Newhaven Community.

The first phase of Restoration Forth (2022-24) was made possible by funding from Aviva, the Moondance Foundation, the ScottishPower Foundation and the Scottish Government’s Nature Restoration Fund, facilitated by the Scottish Marine Environmental Enhancement Fund, and managed by NatureScot.

The current phase of Restoration Forth is made possible by funding from Sky and the Cinven Foundation; the project is supported by the Scottish Government’s Nature Restoration Fund, managed by NatureScot.